"...This first spell in HMS Drake[1] lasted 2 weeks and then my name came over the tannoy to report to the Drafting Office, where I was told I was on draft to a

trawler and to report, with my baggage, the following Monday morning. This I duly

did and was loaded on to a lorry bound for Dartmouth where HMT Notre Dame de

France was berthed. I was relief telegraphist; it was a temporary draft only because

the regular telegraphist had got appendicitis, had gone into hospital for an operation and

would be absent for about 4 weeks. However, some complications set in and it

lasted 7 weeks. Apart from the incessant air raids and an idiot of a liaison officer, it

would have been a super number.

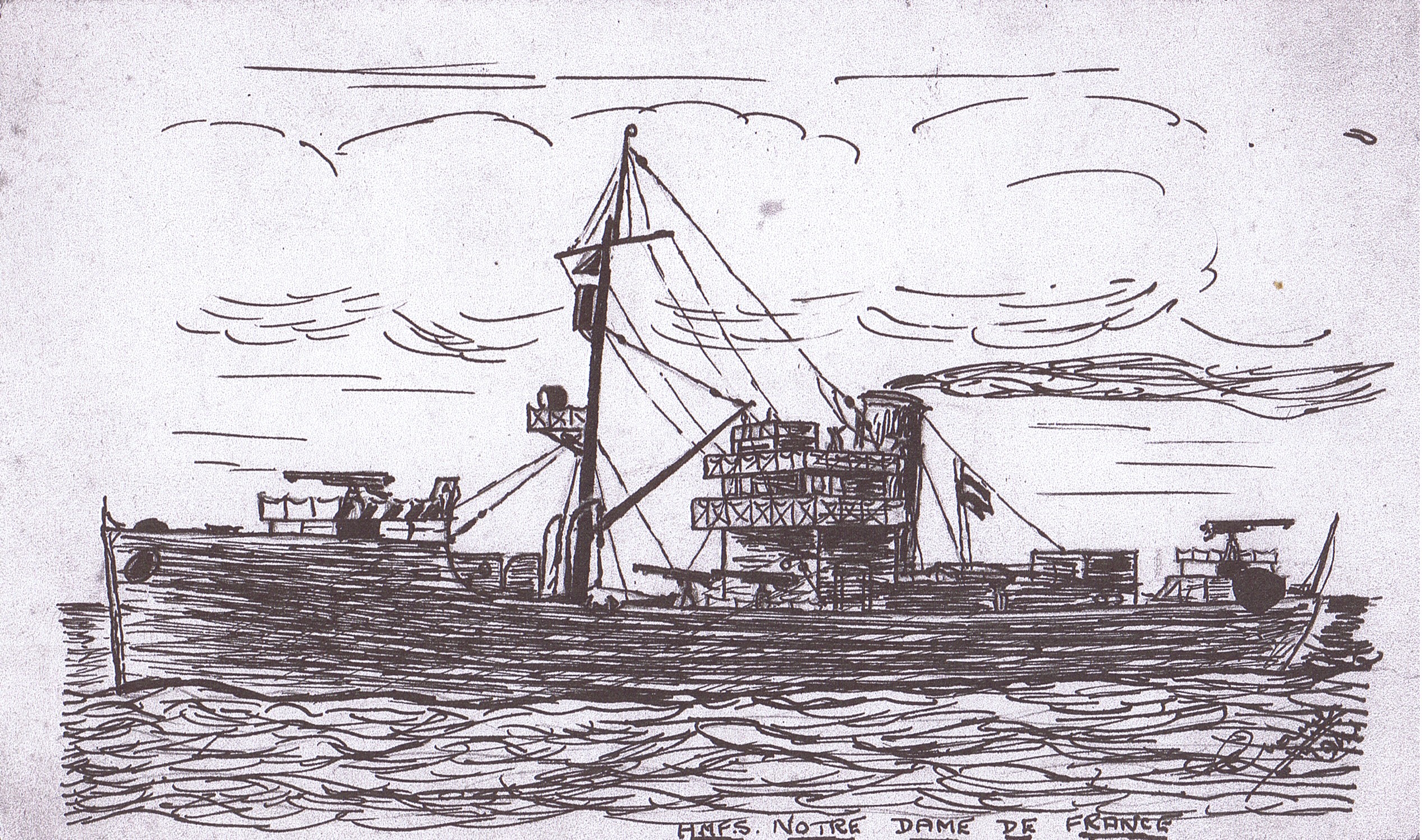

HMT Notre Dame was a French trawler that had got out of Cherbourg around the

time the Germans got in. They’d sailed it to England where it had been

commandeered and given a Dutch crew. I don’t know if the French had armed it or

whether it had been done in England, but it was the heaviest armed trawler I ever

came across - it had four French 75 mm, two twin 12.7 mm Hotchkiss machine guns

and two twin Lewis guns. The Dutchmen were great blokes, very friendly and

helpful.

The food was fantastic and it was a ‘wet’ ship, i.e. bottled beer was

available on ration. The aforementioned liaison officer wasn’t on board when I

joined the ship, as he was in Falmouth. We were picking him up on the following

day, before taking a convoy to Milford Haven which, together with other trawlers

and a couple of destroyers, was our regular chore. His not being aboard was a lucky

break for me, as I had time to get myself sorted out and familiarize myself with the

wireless office and equipment.

I had already used the same transmitter and receiver

in training, and during the 2 weeks in Drake, so I was pretty conversant with that

angle. The wireless office was also my billet and had a narrow bunk along one side

which served as a seat during the day. There was a ladder at one end which led

through a hatch onto the Bridge, and a door at the end of the bunk which led to

another cabin. This was Lt. A’s billet and was always kept locked. Lt. A was a

RCNVR officer and after only a couple of minutes of our first meeting I formed the

opinion that he should have stayed in Canada.

We sailed early on Tuesday morning for Falmouth. The sea was flat calm,

not a swell, not even a ripple, just like a sheet of glass. I never saw the sea like that

again and according to the Dutchmen, it was a pretty rare condition. We arrived at

Falmouth in the early afternoon, as it was only about 75 miles along the coast and

we chugged along at about 12 knots. I’ve forgotten the exact watchkeeping times

for a single-handed wireless office, but I remember I set watch in the morning as we

were under way and also in the afternoon after arriving. (On escort and during air

raids, I seemed to be on watch all the time and got most of my sleep during the day

after arriving at the destinations).

Lt. A didn’t show up until dinner time, which was

about 6.30 pm. He came down to the messdeck during the meal; I don’t think the

Dutchmen liked this invasion of their mealtime, and after the following altercation, I

didn’t either.

We were all eating and chattering away when suddenly everything

went quiet; a voice behind me said “So you’re the relief telegraphist, Grange”. I

think I just turned around on the mess stool and said “Yes, Sir”. He replied, “Then

stand up, turn around and stand to attention when you’re speaking to an officer!”.

I thought “My God, we’ve got a right one here!”. He then took exception to me taking

a bottle of beer with my dinner and as there was nothing else available except water

at that particular meal, I thought I was justified. He asked me if it was Royal Navy

custom to drink beer on the mess deck and I said no, but I was on a Dutch ship and

the rest of the crew were drinking it, so I was too. I also pointed out that there was

nothing else to drink but water and that my predecessor had taken the beer, so I

didn’t think I was doing anything out of order.

However, the twit said I was out of order in doing so. I took old Chiefy Shell’s advice on standing my corner against

supercilious officers and said if I couldn’t have the beer, could he arrange for my

rum ration to be brought aboard as I was a ‘grog’ rating and not getting the

threepence per day in lieu.

At this point, one of the Dutch Ldg Hands stood up and

said “Excuse me Sir, but this is our mealtime and some of us soon have to be on

watch”. I thought he was going to have a fit, but he just tumed around and left, and I

continued with my dinner. I later asked the base CPO Telegraphist if I was in order and he

said to “Carry on, the guy’s an idiot.”

We sailed again that Tuesday evening with a convoy of merchantmen and a

few other trawlers for Milford Haven. I’d gone on watch at about 8 pm as we sailed

and didn’t come off until about 09.00 the next morning. I’d received the air-raid

warnings in the usual sequence, yellow - amber - red, starting about 9 pm. It stayed

at red all night, and it was an active red. Our guns were going most of the night and

I was surprised they had any ammunition left the next morning. I think a couple of

ships were hit, but none were sunk.

It was the same every night we were at sea,

some ships were sunk, a few German aircraft were shot down and I didn’t know if I

was coming or going. I wasn’t getting much sleep and when we were in harbour

there was the maintenance to do, aerials to check for bomb splinter damage,

batteries to see to, etc. The crew was in two watches and even though they worked

like Trojans during air raids, they had plenty of time to catch up on their sleep. At

the end of the 7 weeks, I was really choked off with German air raids.

Another little altercation I had with Lt. A was about my correspondence. At

this time, I was exchanging letters with a pal who I had worked with before joining

up. He’d gone into the Royal Engineers about 3 months before I’d joined up. He

did his 6 weeks basic training and they put him and his unit on a ship, took them to

Georgetown, British Guiana, and he stayed there for the rest of the war.

He had a

super time and never saw a shot fired in anger. He came home with a lovely suntan

and a photo album of the families he had stayed with in the country, etc. and the

places they’d shown him. We had a good line going in dirty jokes and always

included one in our letters.

It was Lt. A’s job to censor my mail and he took

exception to my jokes. He came into my office one day and said a particular joke

must be censored out, and would I stop writing them as they offended his feelings.

I

stood my corner again and said that as it wasn’t a service matter or a breach of

security he had better leave it in. He didn’t like being crossed (if he’d known how

scared I was of talking back he might have pressed his point) but he backed off

again and I know the joke was left in, because my pal remarked on it in his return

letter. I never posted anything aboard again, but always went to the base postbox.

The final bust up with Lt. A came one night at sea; we were in a particularly

heavy air raid, two ships had been sunk and I got a signal to detach and search for

survivors. I went up the ladder to the bridge hatch and found it fastened. I tried the

door into A's cabin, but it was also locked, so I got a hammer and hammered on the

hatch.

It was opened up fairly quickly and I went on up to the bridge, but the short

delay had made us a bit late in performing the manoeuvre to detach. It wasn’t my

fault, although it was possible I could get the blame for slow operating, but what

concerned me more at that time was that the hatch onto the bridge was my escape

route in case of an emergency. I asked ‘A’ who had authorized it locked.

The crackpot said he had, as he didn’t think I would stay on the set long enough to get a

signal off if we did have an emergency. I replied that I wouldn’t need to get a

signal off if that happened, as there were enough damned ships around to see what

was going on. I also asked him what he would be doing in such a situation; would

he be hanging around to unlock the hatch to let me out after thinking I’d had enough

time to get a signal off?

The Dutch skipper didn’t think much of A’s action, so he mustn’t have

known about it, or he wouldn’t have allowed him to do it. I told the base CPO Telegraphist

at Falmouth and he reported to a higher authority. ‘A’ got a reprimand a few days

later and I got to know through feedback from the CPO.

I didn’t have much chance

to see if it made any difference to his attitude, as only a couple of days after we were

on a convoy to Milford Haven when we had a near miss which stove in some side

plates on the port side.

The ship started taking on water rather quickly and

developed a list. ‘A’ told me to get the confidential books and codes and put them

into a weighted bag ready for sinking, and to get ready to abandon ship.

A few

moments later we went over the side into a Carley float, but I kept hold of the books

and it was as well I did, as some of the crew had got a collision mat over the side

pretty quickly and, whether by good luck or whatever, the water rushing into the

ship had pulled the mat over most of the damage.

The water was checked and it got

to the stage where the pumps were throwing out more water than was coming in.

After a couple of hours we went back aboard and staggered around to Milford

where, sometime during the next day, we went into dry dock for repairs.

|

| HMT Notre Dame - pen and ink sketch from memory, 1941. |

Each watch was to get 2 weeks leave and I dropped lucky for the first lot. However,

I’d only been home a couple of days when I received a wire ordering me back to

Milford to pick up my baggage and a rail warrant, and to report back to Drake as I

was on unentitled leave, having had my end-of-training leave only a few weeks

before.

This I duly did, but what with air-raid warnings holding up trains, etc. it

took me all of 3 days to get back to Drake. When I reported to the Regulating

office, tired and grubby after all that messing around, the duty PO asked me what I

thought I was up to, taking extra leave. I said I didn’t think it was extra, I was

ship’s company and thought I was entitled to it, and if he’d been offered it in the

same position would he have refused it?

“Go on, you cheeky young bugger, get off

back to Grenville Block”. Apparently, if I'd been on permanent draft to the ship

everything would have been ok, but being only a relief, the rules were different.

So started another hair-raising period of air raids as, just at that time,

Plymouth was a major target for the Luftwaffe. For the next 4 to 5 weeks, which

was the length of my stay in Drake, almost every night saw a heavy raid in the area.

Nights in depot were spent either in the basement, fire-fighting, rescue or

ammunition carrying.

If you were unlucky, you went into the basement shelter, but

most nights I was ‘aboard’ I managed to get an outside job. I didn’t go much on

being fastened up in a basement and I volunteered for anything going to keep me in

the open air.

It was during this 4-5 weeks that Boscawen Block, just across the

roadway from Grenville Block, was flattened, and unfortunately that night I was in

the basement of Grenville Block.

About 2 am, alter 4 hours of continuous bombing

and gunfire, there was an almighty crash, our ceiling came down and the building

shook. After about half an hour, a PO came down the steps from outside and said

he wanted us all outside on rescue work.

What a sight when we got to the front of

the block. Boscawen, which had been a massively built, four-storey building, didn’t

have a wall left above 4 feet high; the only things above that height were the two

door pillars and the lintel. There were about 450 Artificers in it at the time and none

survived.

There was some speculation as to what had been dropped to cause such a

collapse of the building, as it had fallen in on itself and there was very little debris in

the roadway round the block. The most popular theory was that it had been a

parachute land-mine which had dropped through all the floors before exploding in

the basement. The building had partly withstood the explosion before collapsing

inwards with the suction.

They were digging for bodies for some time alter that, but

I don’t think they had got many out before I went on draft again, and this time to a

real warship..."

Notes

[1]: HMS Drake was the name given to the Royal Navy barracks at Devonport (Plymouth).

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()